Vesicovaginal Fistulæ

Causes

- Obstetric complications: most common worldwide (0.09-0.66 per 1000 pregnancies)

- Iatrogenic: more common in countries with better medical resources, caused by injury at time of pelvic surgery

- Hysterectomy: most common cause of iatrogenic fistula (60-75%), prevalence 0.1-4%, more common with abdominal approach

- Obstetric fistulas more likely to be larger and distally located, involving bladder neck and proximal urethra

- Ketamine abuse has been shown to cause bladder changes and fistula formation

VVF Prevention Principles During Pelvic Surgery

- Immediate detection of bladder injuries

- Watertight bladder closure

- Extravesical drain placement

- Avoid vaginal incisions

- Maintain prolonged bladder drainage

Diagnosis

- Most common symptom is persistent urinary drainage via vagina

- Leakage may be positional if fistual is small

- Pain is uncommon unless severe skin irritation present or history XRT

- Anterior wall is most common location, consider presence of inflammation/infection (may delay repair)

- Consider instilling methylene blue into bladder and looking for staining on tampon, ambulation may increase sensitivity of test

- Double dye test: PO pyridium + intravesical methylene blue, detects ureterovaginal (orange) vs vesicovaginal (blue) fistulas

- Perform cystoscopy, consider biopsy if history of malignancy (may be recurrence)

- CT/MR may show delayed contrast drainage into bladder, may be beneficial to assess for ureterovaginal fistula (CTU)

- VCUG/cystogram can be performed, but needs to show voiding or postvoid images

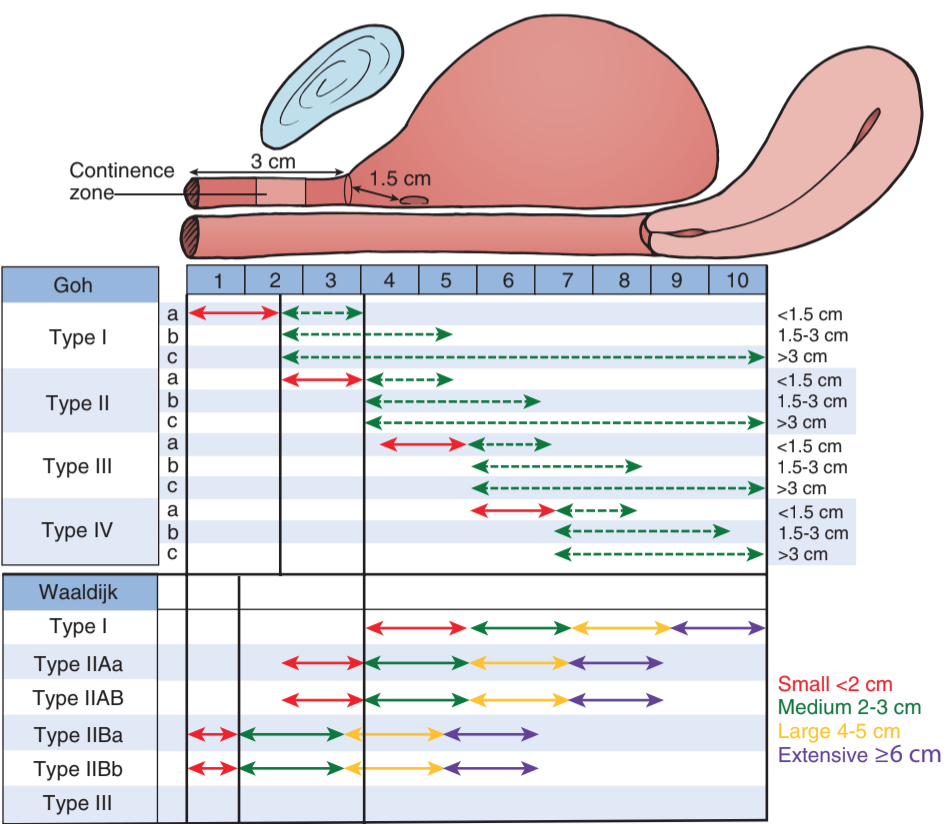

- Use fistula classification (see Goh image) to assess severity

Treatment

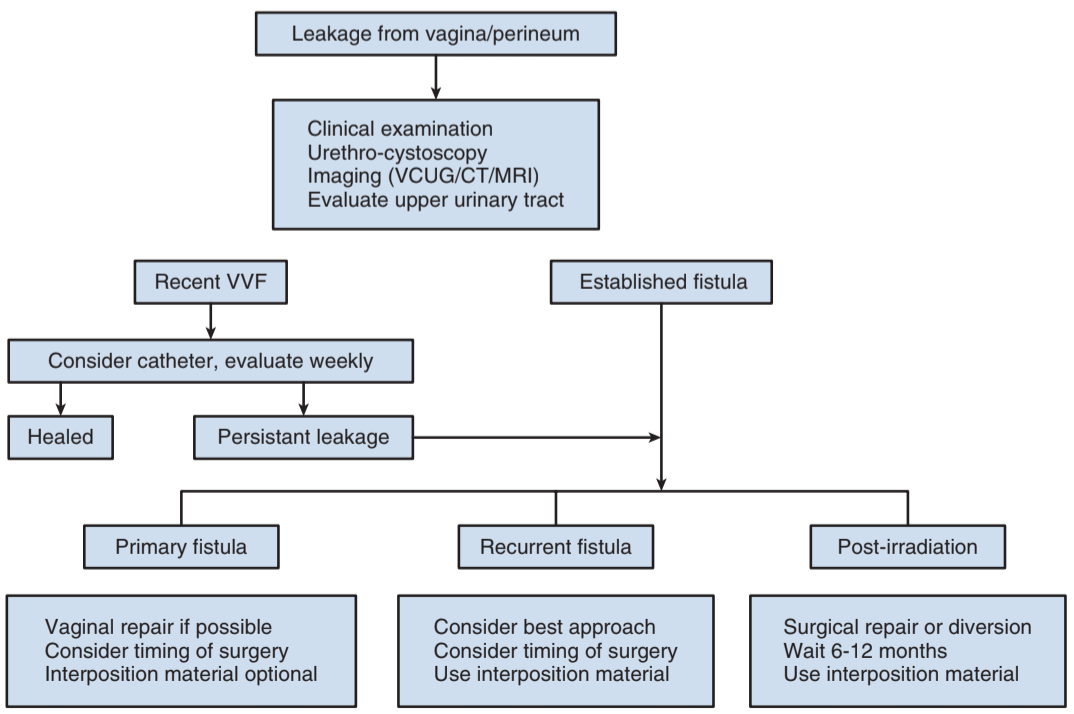

- Consider foley + anticholinergics for 2-6 weeks for fistulæ < 1cm

- Consider electrocoagulation for small (< 3-5mm) fistulæ

- Either time repair for 2-3 weeks after diagnosis, or 2-3 months if outside initial window

- Abdominal vs vaginal approach is mainly affected by surgeon preference

- Vaginal approach may cause vaginal shortening, affecting sexual activity

- Leave catheter for 2-4 weeks, consider cystogram prior to removal

- 85% success rate for primary repairs

- Complications: bleeding, compromised flap blood supply, ureteral injury, vaginal shortening/stenosis, fistula recurrence

- Urinary diversion: best if active malignancy, severe XRT damage, or large tissue loss

- If patient is high surgical risk, consider nephrostomy tubes + ureteral occlusion

- Ureterosigmoidostomy: last resort if unable to perform diversion or other repairs

Flaps

- Transvaginal approach: labial fat pad (Martius) or peritoneal flap

- Transabdominal approach: peritoneal or omental flap

- Martius flap: fibrofatty labial tissue best used if fistula involves trigone or bladder neck, does not usually reach vaginal apex fistulæ

- Peritoneal flap: better for high fistulæ, mobilize from anterior culdesac, repair any peritoneotomies

Ureterovaginal Fistulæ

Presentation

- Commonly presents 1-4 weeks after surgery with constant urinary leakage

- Patients will have normal voiding patterns due to filling from normal side, whereas VVF will report constant leakage only

- Preoperative stenting: no change in injury rates (1.2% vs 1.1%)

- Ascitic or extravasated fluid will have elevated creatinine level

- Diagnose with CTU or retrograde pyelogram

Treatment

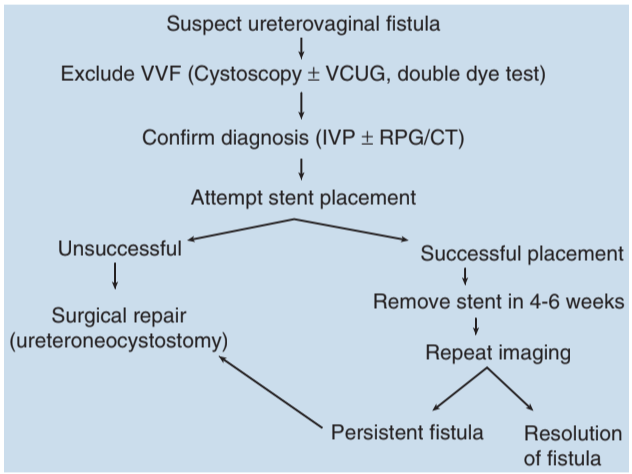

If ureter is patent, attempt stent placement (~50% closure rate)

If unable to stent, place nephrostomy tube and perform delayed repair (4-6 weeks) with reimplantation

Reimplant tips: preserve adventitial layer, tunneling not required

Success rate: 90% after formal repair

Ureterouterine or ureterofallopian fistulæ are rare

Other Female Fistulæ to Consider

Vesicouterine Fistulæ

- Usually caused by simultaneous bladder and uterine injury, C-section is most common cause

- Cervix may act as a sphincter and may prevent expected constant leakage

- Youssef syndrome: menouria, cyclic hematuria with amenorrhea, infertility, and urinary continence in a patient with prior C-section

- Diagnosis: cystogram or hysterosalpingogram

- Consider prolonged catheterization, menopause induction, or formal surgical repair with omental flap

- Uterine-sparing surgery can be performed to preserve future fertility, otherwise perform hysterectomy

Urethrovaginal Fistulæ

- Occurs with prolonged labor, SUI treatments, prolonged catheterization (urethral erosion), or after genital reconstruction

- Distal fistulæ may present as split stream or vaginal voiding

- Diagnose with exam, cystoscopy, and VCUG

- Vaginal repair most commonly used, success rates 70-90% after primary and 92-97% after secondary repair

- Can consider SUI repair at time of fistula repair, with use of Martius flap

Colovesical Fistulæ

Causes/Presentation

- Most commonly seen with diverticulitis (20% patients), Crohn disease (2-6% patients), and colonic malignancy

- LUTS more common presenting symptom than GI - pneumaturia (52-77%), fecaluria (36-51%), UTI (44-45%), hematuria (5-22%), orchitis (10%), urine per rectum (5%)

- Gouverneur syndrome: suprapubic pain, frequency, dysuria, tenesmus

- Pyeloenteric fistulæ: seen with inflammatory disease (XGP kidney) or post-surgical (PCNL)

Diagnosis

- Cystoscopy: provides definitive diagnosis in 35-46%

- CT triad: bladder wall thickening adjacent to thickened colon, air in bladder, and presence of diverticula

- Contrast studies (enema/cystography): surprisingly, less useful for identifying fistulas

- Charcoal study: PO intake of charcoal will demonstrate charcoal flakes in the urine if fistulæ present

Treatment

- If nontoxic, minimally symptomatic, and nonmalignant cause -> TPN, bowel rest, and antibiotics

- Non-surgical approach preferred for Crohn disease due to high risk for recurrence

- Staged repair (ostomy + reversal): indicated for unprepared bowel, gross contamination, or abscess

- Three staged treatment for complex fistulas: proximal defunctioning and distal drainage, TPN + nutritional support, then joint reconstructive surgery

Rectourethral fistulæ

Causes/Presentation

- Seen with prostate surgery (< 1-2%) or XRT (0.4% brachytherapy), malignancy, infection/abscess

- May present with fecaluria, hematuria, UTI, sepsis

- DRE may detect fistula on rectal wall

- Cystoscopy/sigmoidoscopy can confirm diagnosis and may provide biopsy (assess for malignancy)

- VCUG/RUG confirm diagnosis and provide length/location for surgical planning

- Consider upper tract imaging to exclude ureteral injury

Treatment

- Some may heal with catheterization, bowel rest, and TPN - some may require temporary bowel diversion

- One-stage repair: small fistulæ not associated with infection/abscess

- Staged repair: large fistulæ, history XRT, infection, immunocompromise, or inadequate bowel prep

- Success rates 88%, with permanent fecal diversion (11%) and urinary diversion (8%)

- York-Mason: transrectal, transsphincteric repair

Vascular-Related Fistulæ

Renovascular/Pyelovascular Fistulæ

- Commonly seen with PCNL due to intrarenal vascular puncture, also seen with erosion of chronic nephrostomy tube into vasculature

- PCNL risks: transfusion (11%) and surgical/angiographic intervention (1%)

- Presentation: active bleeding with nephrostomy tube removal, sudden hematuria or flank pain (usually 2 weeks after PCNL)

- Nephrostomy tube removal: replace tube or place foley and inflate to tamponade

- IR embolization for unstable patients, nephrectomy rarely indicated

Ureterovascular Fistulæ

- Risk factors: prior XRT, pelvic cancer surgery, pelvic vascular surgery, chronic ureteral stents, less commonly AVM, kidney transplant, pseudoaneurysm

- Presentation: almost always with hematuria

- Diagnosis: angiography only has 62% sensitivity (due to intermittent bleeding or transient thrombus formation), have high degree of suspicion, consider "provocative" angiography (manipulate suspected site)

- Treatment: endoscopic vascular stenting (if stable) or open repair (if unstable)

- High mortality rate (7-23%)

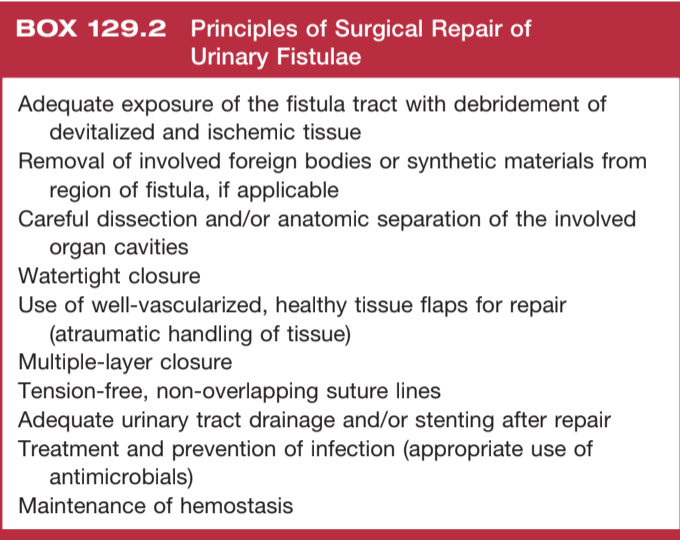

General fistulæ management

General tips

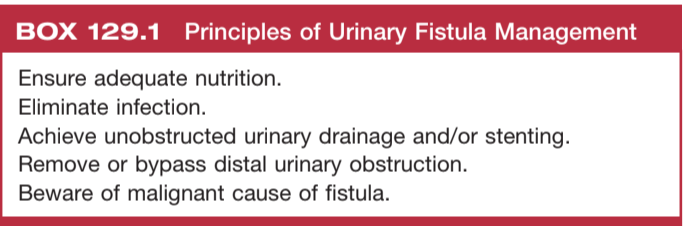

- Consider predisposing/complicating factors: radiation, prior surgery

- Remove distal obstructions, and consider proximal diversion

- Optimize nutritional status, may help fistulas spontaneously close

General postop tips

- Maintain urinary drainage (foley, stent) to maximize healing

- Consider exam or imaging study prior to removing tubes to confirm fistulæ closure

- Consider vaginal estrogen to maximize epithelial healing

References

- AUA Core Curriculum

- De Ridder, D. and T. Greenwell. "Urinary Tract Fistulae." Campbell-Walsh Urology 12 (2020).

- Kamphorst, Kyara, et al. "Arterio-Ureteral Fistula: Systematic Review of 445 Patients." The Journal of Urology 207.1 (2022): 35-43.