Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgery

Optimizing Surgical Outcomes

Preoperative

- Contraindications: coagulopathy, untreated intestinal obsturction, abdominal wall infection, hemoperitoneum, hemoretriperitoneum, peritonitis, malignant ascites

- Obesity: pelvic surgery more difficult with BMI > 30-35

- Pregnancy: 2nd trimester is best time

- Bowel preparation: not required (no proven benefit) but may be helpful to improve visualization in pelvic surgery

Intraoperative

- Palmer point: subcostal at left midclavicular line, best place for Veress needle if prior abdominal surgery (least risk for intestinal injury)

- Ascites: increases risk for bowel injury on entry, ensure tight wound closure to prevent postoperative leakage

- Abdominal aneurysm: consider using Palmer point to avoid placement in aneurysm

- Fascial closure: only necessary for port sites > 10mm in midline, otherwise can close skin only

Access options

- Veress: pass needle perpendicular to skin, draw back then inject saline, upon removal of syringe saline should drop down (drop test), then CO2 can be connected, needle should be able to be advanced 1cm without resistance (not in preperitoneal space), once insufflated can place first trocar with visual obturator

- Hasson: incise infraumbilical and cut through all layers to access peritoneum, place traction stitch in fascia, insert cannula, anchor with traction stitches

- Modified Veress: incise skin and dissect down to fascia, grasp fascia and place Veress into peritoneum

- Trocar placement: incise skin, place trocar with twisting motion (do not push), visualize intraabdominally, angle perpendicular to skin (avoid skivving), once through fascia can angle away from organs

- GI/GU drainage: place catheter and NGT help decrease risk for bladder or stomach injury

Physiologic effects of pneumoperitoneum

- Venous return: do not exceed pressures above 20mmHg, otherwise will decrease venous return

- Cardiac: often see tachycardia, peritoneal irritation can cause vagal stimulation and bradycardia, arrythmias otherwise uncommon, hypercarbia can cause vasoconstriction

- Respiratory: decreased capacity due to abdominal pressure and trendelenberg position, decreased capacity and compliance, can lead to pulmonary edema in patients with elevated left heart pressures

- Acid/base balance: hypercarbia seen in patients with prior pulmonary compromise

- Skin: prolonged trendelenberg position may cause facial swelling and bursting of capillaries

- Renal: oliguria caused by decreased renal flow and direct renal compression, can diurese with furosemide, mannitol (12.5-25g), or dopamine (2ug/kg/min)

- Mesentery: less ileus than with open surgery, decreased mesenteric blood flow can rarely cause delayed mesenteric thrombosis

Complications

Anesthesia complications

- Cardiac issues: use invasive cardiac monitoring for ASA 3+ or heart disease, consider helium use to avoid hypercarbia, immediately desufflate and perform compressions if cardiac arrest occurs

- Hyper/hypotension: if no active bleeding then desufflate abdomen while other causes ruled out

- Gastric aspiration: increased with DM/gastroparesis, hiatal hernia, obesity, consider prophylactic metoclopramide (10mg) and cuffed ET tube, avoid atrophine (decreases esophageal sphincter tone)

- Hypothermia: temperature decreases 0.3C for every 50L CO2 used, provide warmed fluids and active warming, if warming gas then needs humidity also to prevent drying out tissue

Access injuries

- Preperitoneal placement: identify with high pressures immediately, uneven abdominal distension, can manage with Hasson placement

- Vascular injury: 0.1%, identify on aspiration, remove needle and place elsewhere, inspect at low pressure (5mmHg) and hold pressure

- Visceral injury: 0.1%, identify on aspiration, remove needle and place elsewhere, inspect for injuries and bleeding, gallbladder injury may require cholecystectomy

- Hasson injury: rare, can occur if bowel adhesed to abdominal wall and injured during entry

Insufflation injuries

- Bowel insufflation: due to unrecognized bowel placement of Veress, will have uneven distension and flatus

- Gas embolism: caused by injecting gas directly into vessel, patient will have abrupt increased end-tidal CO2 and sudden decline in oxygen saturation, may have millwheel precordial murmur, blood sample may foam, manage with immediate desufflation and put patient in head-down and left lateral decubitus to force air into right atrium, provide 100% oxygen, can attempt central line aspiration of air

- Barotrauma: sudden increase in ventilation pressures, desufflate completely and resufflate at low pressure, ensure machines not malfunctioning

- High pressure devices: argon beam and CO2 laser can create high pressure gases, consider opening outflow during instrument use

- Subcutaneous emphysema: can be caused by gas leakage around ports, patient can develop abdominal/thoracic crepitus (and pneumoscrotum), can place pursestring stitch or balloon trocar

- Pneumopericardium: rare (0.8%), will present with sudden cardiac decompensation, can manage with pericardiocentesis

- Pneumothorax: 1.6-4%, more common with retroperitoneal procedures, decreased breath sounds and hypotension indicate tension pneumothorax, place large bore needle to decompress

Trocar placement injuries

- Intestinal perforation: diagnose by assessing through another port, leave port in place until prepared to repair, repair via open or laparoscopic technique, irrigate abdomen with antibiotic solution, contact general surgery even if repaired by urology

- Vascular injury: 0.11-2%, may be diagnosed on obturator removal and blood return or on inspecting abdomen, open abdomen and clamp proximal/distal with bulldog or Satinsky clamp

- GU injury: 0.02-8.3%, diagnose with pneumaturia or hematuria, can identify cystotomy with instillation of indigo carmine + saline solution, do not leave foley without repairing

- Port site bleeding: identify blood dripping intraabdominally, tilt trocar to identify source, can use Keith needle to suture bolster to skin for compression (without removing Trocar), use port closure device at end of case to provide hemostasis

Intraoperative injuries

- Electrosurgical bowel injury: avoid activating instruments out of view and unnecessary activation, often presents delayed (fever, nausea, peritonitis, hypothermia, leukopenia, persistent pain at trocar site), can attempt management with elemental diet and antibiotics, otherwise exploration and bowel resection

- Mechanical bowel injury: usually diagnosed intraoperatively, can repair intraoperatively, irrigate abdomen with antibiotic solution, undiagnosed injury presents with fever, nausea, ileus, peritonitis, diagnose with CT with PO contrast, delayed diagnosis requires takeback with bowel resection

- Vascular injury: rare, raise pressure to 25mmHg, provide (lateral not top-down) compression, use thrombotic agents, need to determine whether to open and repair, larger injuries warrant vascular surgery consult, consider extra port placement for suction/irrigation

- Nerve injury: 2.8%, can be due to compression, stretching, or direct injury, obtain neurology consult if injury identified postoperatively, if no recovery in days then may require months

- Bowel entrapment: usually delayed diagnosis, presents with ileus and pain at site, replace ports and cut skin stitches then replace bowel in abdomen, rarely requires bowel resection

- Pancreatic injury: 75% diagnosed postoperatively, presents with pain, elevated lipase/amylase levels, use NGT+TPN and drain placement, remove drain once < 50mg/d output then remove NGT, prevent with wide mobilization

- Splenic/Liver injury: can manage intraoperatively with hemostatic agents or argon beam, prevent with wide mobilization and retracting on ligaments (not directly on spleen)

- Bladder injury: may notice air/blood in catheter bag, identify intraop by instilling dye via catheter, identify postop via cystography

- Ureter injury: may notice intraop due to lack of efflux on cystoscopy or extravasation, can repair intraop, postop diagnosis via CT urography or retrograde pyelogram

- Diaphragm injury: diagnosed intraop with billowing diaphragm, may note desaturations, tachycardia, or cardiovascular instability from tension pneumothorax (decompress), close defect after evacuating pleural air, may require chest tube, can manage postop with CXR and supplemental oxygen +/- chest tube placement

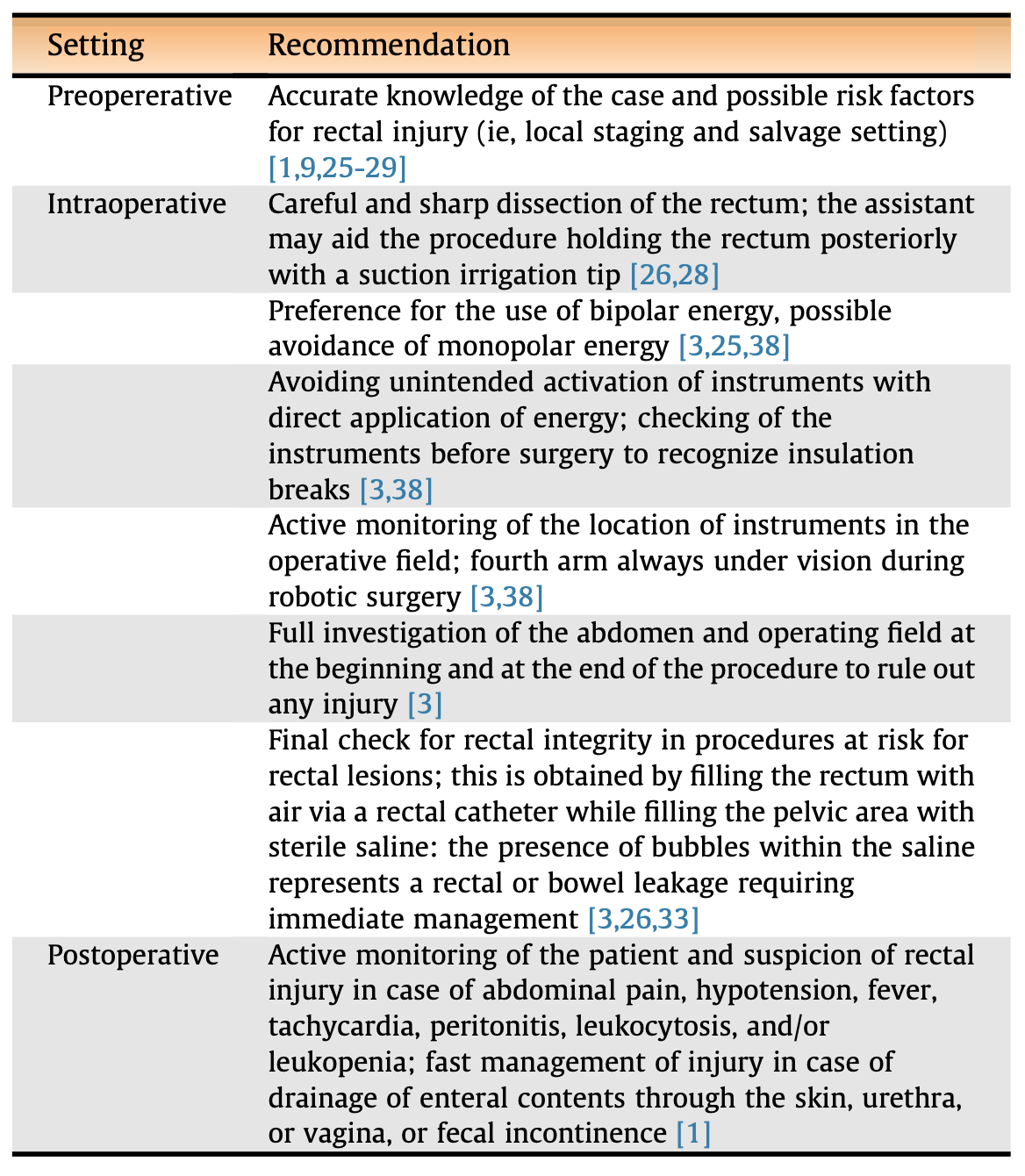

Rectal injuries (from Rocco 2022)

- Risk factors: prior surgeries (loss of planes), prior XRT, locally advanced cancer, salvage surgery, surgeon inexperience, prostate biopsy within 1 month

- Prevention: avoid cautery (emphasize sharp dissection), be aware of instrument location at all times,

- Intraoperative repair: irrigate with saline/betadyne, clearly delineate injury (may require DRE), close in 2 layers with 2-0/3-0 vicryl, may close additional layer with perirectal tissue, place omental flap especially if performing prostatectomy anastomosis nearby, check for leak with instilling air into saline-filled field or perfoming sigmoidoscopy

- Postoperative presenting symptoms: abdominal pain, hypotension, fever, tachycardia, peritonitis, septic shock

- Delayed diagnosis of rectal injury: KUB may show free air, CT w/ rectal contrast

- Post-repair management: liquids immediately with diet after return of flatus, antibiotics for 5-7 days

- Indications for bowel diversion: no clear indication, consider if history of XRT, need for bowel resection, concern for fistula

Postoperative complications

- Intraabdominal bleeding: hypotension, tachycardia, high drain output, dizziness, oliguria, abdominal distension, requires surgical takeback (occasionally can use embolization)

- Port site bleeding: painful port site ecchymosis, CT demonstrates abdominal wall hematoma, rarely requires embolization or exploration

- Port site pain: can be due to hernia, bowel injury, infection, or hematoma

- Scapular pain: diaphragmatic irritation from insufflation

- Incisional hernia: presents with pain, nausea, and ileus, diagnose with CT, will require surgical hernia repair

- DVT/PE: prevent with SCD use, chemoprophylaxis in high risk patients

- Wound infection: rare in laparoscopic surgery

- Rhabdomyolysis: 0.4%, avoid prolonged positioning and hypotension, presents with pain, brown urine, and CK > 5000

- Lymphocele: occurs with pelvic surgeries, presents delayed with pain or DVT, diagnose with CT, manage with drainage +/- sclerotherapy, may require laparoscopic marsupialization

- Chylous ascites: CT will demonstrate ascites and tap will show elevated fats, manage with low-fat MCT diet, can consider somatostatin or octreotide, rarely requires surgical management

References

- AUA Core Curriculum

- Ghavamian, R. and C. Chalouhy. "Complications of Urologic Surgery." Campbell-Walsh Urology 12 (2020).

- Patel, R., K. Kaler, and J. Landman. "Fundamentals of Laparoscopic and Robotic Urologic Surgery." Campbell-Walsh Urology 12 (2020).

- Rocco, Bernardo, et al. "Rectal perforation during pelvic surgery." European Urology Open Science 44 (2022): 54-59.